My volunteer work at the moment is focused on the village planning projects with the Ministry of Works and Human Settlements (MoWHS) (my other jobs either being complete or having taken a back seat for a while). Given that I’m currently on a uni break and working more in the MoWHS office, they’ve also asked me to prepare some conceptual designs for modern buildings but in the traditional Bhutanese style, for some steep sites in a new village in the far East of Bhutan. So it seems an appropriate time to write a long overdue post on Bhutanese architecture.

Traditionally, buildings in Bhutan have always been built without plans by skilled craftsmen who pass on their knowledge and skills from generation to generation. Qualified Architects in the modern western sense are a relatively new phenomenon in Bhutan. The Senior Planner I report to in the Department of Human Settlements, Mr. Ugyen, (6 years my senior) studied Architecture in India and when he returned to Bhutan with his qualification, was the 13th Architect in Bhutan! (There are now around 70 qualified Architects in the whole of Bhutan). He went on to obtain a Masters in Urban Planning from the University of South Australia in 2001 and now heads the Regional Planning and Development Division within the Department. This is a team of only 6 people who are responsible for planning throughout the entire country outside of the few major urban centres. This is an area roughly comparable in size to the Hunter Valley and Greater Sydney combined, but with a population size similar to the Hunter region only, spread across some of the most inaccessible and rugged terrain in the world.

To date there are no Architecture courses offered in the colleges and Universities of Bhutan, so all Bhutanese Architects qualify overseas. There is a huge emphasis on education in Bhutan lead by a push from both the Monarchs and the Government. The Government provides a lot of scholarships to Bhutanese school leavers to enable them to further their education abroad. The Australian government has also been providing scholarships for Bhutanese students to study at Australian Universities since the 70’s under the Colombo Plan. I met the Vice Chancellor of the Royal University of Bhutan (RUB) at the launch of the Bhutan Australia Alumni Association last month. He was one of the first to study in Australia. He was sent to Perth as a young boy to complete high school followed by a university undergrad degree in teaching. These days the Australia Awards program focuses on Masters and PHD scholarships. This year the program received over 400 applications for a possible 50 scholarships. Australia is a very popular destination for Bhutanese wishing to further their studies. Recently it was announced that the same program will soon be supporting Australian students to study in Bhutan. While Architecture is not yet offered here, Engineering (civil, electrical, electronic & IT) is offered at the College of Science and Technology in the southern city of Phuentsholing. The first law school for Bhutan is currently being established just outside Paro. And according the VC, the Royal University of Bhutan may be offering Architecture in the near future.

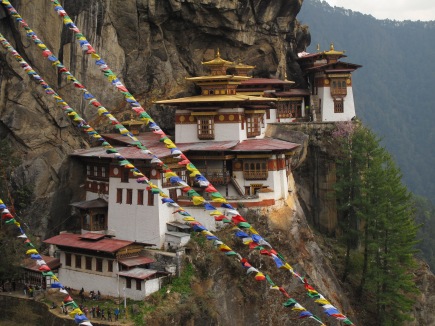

I recently met the current president of the Bhutan Institute of Architects (the professional association for Architects in Bhutan) Ms Dorji, who completed her Architectural studies in Australia. One of her first projects when she returned from Australia as a junior architect with the Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs (MoHCA), was the reconstruction of what is probably Bhutan’s equivalent of the Sydney Opera House in terms of iconic status: Taktshang Monastery near Paro, which had been destroyed by fire in 1998. This is the one you see in all the promotional images of Bhutan – it not only clings almost impossibly off the side of a cliff, but is also shrouded in significant Buddhist myths and legends. She explained to me how they set up a camp at the base of the cliff with a temporary office, sleeping huts, material storage and construction area. No measured drawings or similar documentation of the structure had been recorded so for the reconstruction efforts they had to go off old photos and diaries. Apparently a call went out worldwide to people who had visited Taktshang appealing for photographs. From these, a detailed scale model was built at the base camp rather than plans (as the Bhutanese craftsmen couldn’t read plans). The materials were then winched up the cliff on a pulley system, and the full sized version constructed over the course of 5 years.

It is extremely encouraging that both Ugyen and Dorji share a strong commitment to do all they can in their respective positions to ensure the traditional Bhutanese architecture survives and thrives despite the emergence of the cheaper modern building materials of concrete, steel and glass and the influence of western values that are more and more prevalent, particularly in the capital, Thimphu. One of the initiatives to encourage this is the provision of subsidies for the use of traditional building materials. Such incentives will form part of Bhutan’s first Planning Act which is currently being drafted by the MoWHS.

Buildings in Bhutan are traditionally built of rammed earth, stone and timber, and their style is quite distinct and very unique. There are 3 main types of building: the large imposing Dzongs (fortresses) which are the municipal and religious headquarters in each district, houses which are predominantly large rural farmhouses and religious structures of various kinds (from large temples to small chortens or stupas).

Dzongs

Before Bhutan was unified under a monarchy in the early 20th Century, the country’s 20 or so districts (Dzongkhags) were ruled by Governers (Penlops). Many battles were waged over the centuries by Penlops for control over neighbouring districts or from neighbouring Tibet so the Dzongs were not only the administrative and monastic headquarters for each district, but primarily acted as fortresses in these battles for control. So naturally they are massive imposing structures and often positioned in strategic locations on traditional trade routes between districts as their other function was to collect taxes in kind (rice, yak meat, woven fabrics etc) from travellers passing through.

The legendary Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal who came to Bhutan from Tibet in the early 17th Century is credited as the great Dzong builder. While some have suffered from fire or flood and been re-built over the years, the Dzongs remain as the important headquarters for each district and also now of course, important tourist attractions.

While each one is different there are some common characteristics. They generally have a central tower called an utse. Surrounding the utse is a central paved courtyard. And surrounding the courtyard is 2 or 3 storeys of rooms looking onto the courtyard. It is generally divided into two wings, one for the monastery containing the temple and monk’s quarters and the other for the district government offices. The external walls slope inwards (battered walls) enhancing how visually imposing the Dzongs appear. They are constructed of either stone or rammed earth and then whitewashed except for the distinctive dark red band around the top part of the walls (kemar) with intermittent white or golden circles.

Dzongs have what’s known as a Jabzhi roof, a square lantern shaped structure with pitched roof on top of the main roof which is yellow or gold in colour. It is decorated at the corners with carved garudas or alligators and crowned with a sertog (a golden cupola). These types of roofs are reserved for Dzongs and religious architecture and are not permitted on houses.

Typical house

The typical traditional house in rural Bhutan is 2 or 3 storeys where the ground floor houses the animals and the upper floors house the family, with an open sided attic (shambarnang) for drying things like corn and chillis. The attic is usually accessed via a steep ladder carved out of a whole tree trunk. Bhutan is traditionally a matrilineal society so houses and property are passed down through the female line. When a couple marries, the husband moves in with the wife’s family.

The walls of the lower floor is traditionally constructed of stone (eastern Bhutan) or rammed earth (western Bhutan) which is pounded by hand and either left in its natural colour or rendered with lime and whitewashed. We stopped to watch some women pounding a rammed earth wall on our ride around the Punakha valley in June. They were singing in order to create a rhythm as they pounded away with their hand held wooden paddles.

The most striking feature of a Bhutanese house (and most buildings for that matter) is the window assembly, known as a rabsel. There are various styles, but it is typically a timber framed structure which wraps around three sides of the upper floors jutting out over the lower storey. It incorporates the windows and has an elaborately carved cornice feature. Traditionally the windows were not filled with glass, but rather timber shutters. The wall space between the windows was traditionally infilled with woven bamboo and then plastered with mud, wattle and daub style (shaddam).

Traditionally the pitched roof is clad with wooden shingles held down by stones but more commonly these days they are being replaced by corrugated iron. The crowning feature is a white prayer flag on the centre of the roof of the house. The strip of blue cloth at the top represents the sky, the yellow at the bottom the underworld and the red in the middle the space between the sky and the earth.

The exterior and interior of Bhutanese houses can be highly decorated. The timber window frames are painted with floral and animal motifs and walls with auspicious symbols such as the Buddhist swastika and the phallus.

With the abundance of forests it’s not surprising that Bhutanese houses and temples have some beautiful timber features: heavy tongue and groove doors with high thresholds you have to step over, exposed carved beams and the widest and most beautiful floorboards, naturally polished by the passage of generations of feet passing over them.

Religious structures

Religious architecture in Bhutan includes Goemba (Monasteries), Lhakhang (Temples) and various types of Chortens (stupas). Monasteries and Temples are similar in structure and design to Dzongs but on a smaller scale. Like the Dzongs, they tend to have the distinctive white washed walls with the dark red band (kemar) around the top, the elaborately carved and colourfully painted rabsel window assembly and the golden Jabzhi roofs.

The most breathtaking aspect of monasteries and temples however, is their interiors. The walls are decorated with detailed colourful paintings depicting Buddhist teachings, called thankas. They are initially painted on stretched canvas and then stuck to the walls like wallpaper, so if a wall needs repairing or rebuilding, the thanka can be carefully peeled off, rolled up and stored and then reinstated on the repaired wall.

Similarly the altars in the temples and monasteries are amazingly elaborate. They tend to be colourfully painted carved timber cabinets filling an entire wall and housing statues of eminent Buddhist figures. In front of them will be a table to make your offerings of money or food amongst the butter lamps and burning incense. And above, colourful fabrics hang down from the ceiling.

Chortens on the other hand are not really buildings but sculptures containing religious relics – you can’t enter them, instead you walk around them. But you must walk in a clockwise direction otherwise its bad luck! They are often found in places considered inauspicious to ward off evil spirits, such as road junctions and mountain passes.

The National memorial chorten in Thimphu is in the Tibetan style (ie its more rounded than the Bhutanese simpler squarer style) and was built in honour of the 4th King. At all times of day and into the evening you can find the elderly people of Thimphu doing laps chanting their prayers in time with their spinning hand held prayer wheels or as they shift their prayer beads along a string.

One of the beautiful things about hiking in mountains in Bhutan is that whenever you cross a stream, you’ll likely find a ‘mani chukor’. This is a type of chorten build over the stream with a prayer wheel inside it and where the water has been redirected through the structure to turn the prayer wheel. With each revolution of the wheel a little bell rings.

Another type of chorten is linear in shape, (known as mani walls), and are often found on the old walking trade routes between districts. Locals will make mini stupas the size of a fist from clay to place inside these walls in memory of loved ones who have passed away. The tall white clusters of vertical prayer flags adorning hillsides and mountain tops where they catch the wind are for the same purpose.

Modern building and construction

Most new buildings in Thimphu are constructed of concrete, glass and steel which are now more readily available. By law they still must incorporate aspects of traditional Bhutanese architectural decoration which is done with mixed success and questionable quality e.g. a simplified version of the rabsel is fashioned out of concrete around conventional aluminium window suites.

Due to a shortage of Bhutanese labourers, most of the construction workers are Indian labourers who typically eat, sleep and wash in makeshift huts on the building site where they work. They come from the poorer Indian states and by coming to Bhutan can earn up to 3 times what they would back home. The women can often be seen sifting and shifting the gravel by hand, sometimes with babies strapped to their backs as they work, while the men are laying and levelling the concrete.

Construction in Bhutan, as with most developing countries, exhibits what would appear to the western eye to be shocking disregard to work health and safety standards. I’ve certainly seen some doosies walking around Thimphu over the last 6 months. Here’s some of my favourites:

Here a worker is jack hammering the edge of a 2nd storey suspended concrete slab (no PPE no scaffolding):

In this one, workers are site welding roof trusses … on the top of a 6 storey building:

And my all-time favourite: this footpath is adjacent to the construction site where the new headquarters for the Bhutan National Bank is being built. The ‘site safety fence’ separating the footpath from the sheer drop down into the construction site is woven bamboo matting. To stabilise the steel reinforcing bars while forming the concrete columns for the new building, the re-bars are tied back with ropes through the ‘safety fence’ and across the footpath to re-bars drilled into the gutter, creating the perfect trip hazard for pedestrians!